I woke up early and drove 40 minutes west on one of my first assignments as a volunteer for a refugee resettlement agency. I picked up an elderly woman from South Sudan and drove back east, the morning sun in our eyes. No words were spoken, as I knew only English and she, only Moro. I had never heard of Moro until that day and Google Translate was no help.

We arrived at the eye clinic shortly before her 8:30 cataract surgery, but the clinic was not yet open. We waited until the door was unlocked at 9:00 and went inside. The trouble began when I walked to the desk to get her checked in. There were three problems: her appointment was at 6:30am, not 8:30am; her appointment was at their surgical center many miles away, not here at the clinic; and finally, the appointment had been cancelled because their attempts to confirm with the patient by phone had gone unanswered which is common when the patient does not know English.

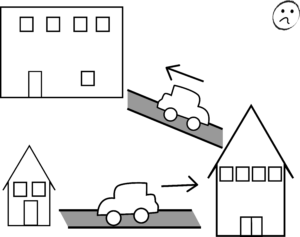

I requested the address of the surgical center; it was another 40 miles to the northwest. It would be a waste of time to drive there, but I couldn’t face driving her home without any means of explaining why. On the back of a random piece of paper, I drew a frowny face and a crude map that showed us going to another location. She nodded, perhaps understanding. Off we went.

At the surgical center, I again approached the check-in desk to explain our case. The woman listened carefully and said she would have to speak to the Director. Meanwhile I looked up at the large flatscreen monitor on the wall showing the names and status of the many people already waiting for surgeries that day.

Within moments, I had the opportunity to explain the situation to the Director. I could see the wheels turning in her head. The Director looked at the monitor on the wall, then down at the refugee woman who returned the glance. I had never heard of a walk-in surgical appointment and I had low expectations. The Director asked, “Has she been taking the eye drops that she’s supposed to take for twelve hours before the surgery?”

“Almost certainly not”, I responded. I had seen no eye drops.

“Hmm … OK”, she replied. “I’ll take her in the back and we will look after her.”

Two hours later, the refugee woman was wearing dark sunglasses and I was driving her home. I wondered what events had shaped this Director’s life that she would set aside the scheduling miscues, the language barrier, the full schedule, the eye drops — and simply do the right thing with grace and determination. I like to think there was a hidden connection formed that day between these two women, who had never met but perhaps shared a sense of common struggle. And I can only wonder if the entire staff captured the vibe and attended to the refugee woman like royalty.

The Director and staff at the surgical center did not see the impossibility – they saw a need and they figured it out. Humanity, kindness, and a little persistence is more powerful than any obstacle.